Roma Ineffabile A Visual Essay on the Eternal City

by: Richard Lucas

For nearly 200 years, from the mid 1500’s to the early 18th century, Rome witnessed an unprecedented population and construction boom. In 1736 Pope Clement XII commissioned a new survey and plan of the city to document this growth and inventory its religious structures, as well as its palaces, squares, monuments and residential blocks. Chosen for the task was Giambattista Nolli, a surveyor from Lombardy, who had worked for the Milanese and Piedmontese governments. In 1748, under the papacy of Benedetto XIV, the Nolli plan of Rome was printed, consisting of twelve plates, each roughly 13″ x 22″, and a catalog listing the city’s various structures.

Unlike the picturesque views or aerial perspectives of cities preferred at the time, Nolli rendered Rome in a completely flattened, overhead view. In this manner, he could more completely illustrate the urban fabric of streets, squares and gardens, and could also show the internal spaces – the courtyards, entry halls, grand rooms, naves, aisles and chapels- of the palaces, cathedrals and public institutions as well. Indispensable at the time as a document for redistributing taxes and in reorganizing the city’s social and juridical administration, Nolli had created an icon of urban design and planning. For the quantity and graphic presentation of information, its originality and technical execution, Nolli’s plan has inspired countless architects, designers, artists and exhibitions since its publication some 250 years ago.

The Italian Ministry of transportation held one such exhibition, titled Roma Interrotta, in 1978. They invited twelve internationally recognized architects to participate and provided each of them with a plate from the Nolli plan. Asked to imagine an ‘interruption’ in the development of Rome since Nolli’s time, the designers had to propose a new, alternative design for the city, using the assigned plate as their canvas. Some envisioned sweeping changes, others reworked very little; some proposed elaborate gardens or revised entire street patterns, while others inserted more monumental buildings or wrote treatises on the tactics of urban design. Although the exhibit never produced a unanimous manifesto on urban planning, it generated discussion on the development of modern cities and promoted an interest in the principles of traditional city planning.

Five years ago, at the suggestion of a colleague, twelve younger architects from New York, myself included, joined together for a similar exercise. We had studied in either Florence or Rome, and found ourselves eager to test our education, ideas and experience. After each receiving a plate to revise, we arranged to meet periodically to discuss architecture, urban issues and, of course, the design of our plates.

I received Plate V, comprised mostly of the Campo Marzio, the central and most densely built area of Rome. Containing the Pantheon, Campidoglio, several Renaissance churches, and a large portion of the Roman Fora it is also among the most historically significant areas of the city. Lacking a strategy with which to begin, I looked to historical plans of Rome for inspiration. Rodolfo Lanciani’s Forma Urbis Romae came to mind, with the buildings of a specific era rendered in different colors. I also thought of Piranesi’s Ichnographia and Il Campo Marzio dell’Antica Romane, in which he recomposed the Campo by filling it with a fantastic array of Roman-like structures. Though they bare little or no relation to specific buildings, the engraving overall still resembles an authentic plan of Ancient Rome. Then, of course, there is Freud’s quote from Civilization and its Discontents, a notion I have always found loaded with haunting possibilities.

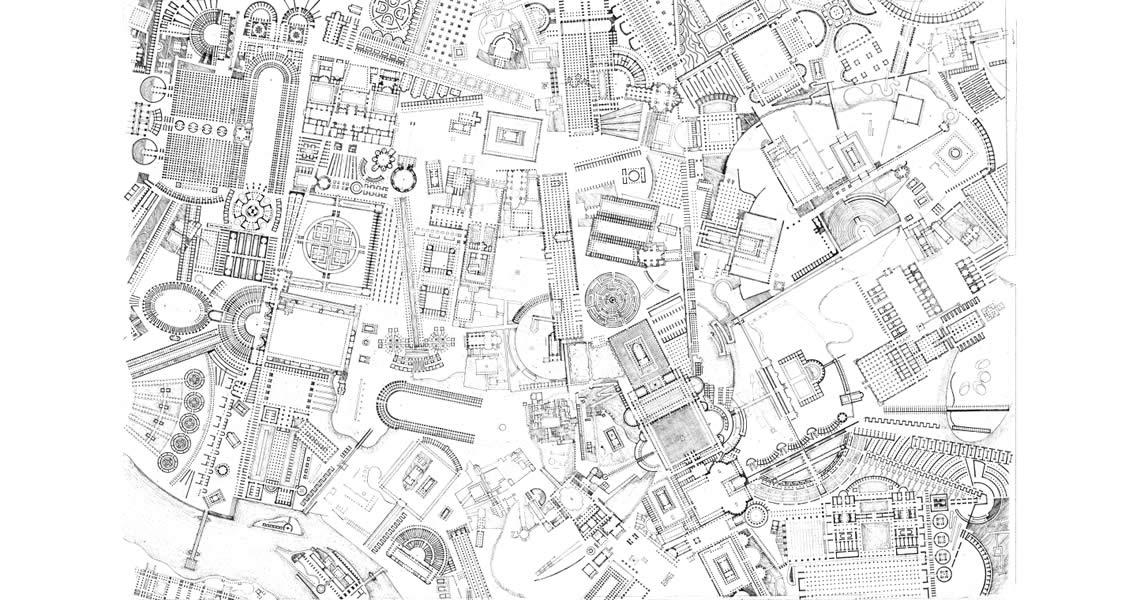

I began the exercise then by collecting the floor plans of several buildings and structures constructed within the Campo. These plans were then ‘edited’ and traced over onto one drawing, creating a collage of Rome’s building history. The nave of a Renaissance church combined with the foundations of a Roman temple, or the courtyard of a medieval housing block. Places or buildings well known like the Forum of Augustus, or the Piazza Navona fused together with the foundations of a more ancient past or some remote future. I added other buildings from throughout the Empire, pieces of Hadrian’s Villa, the Acropolis, temple complexes from Pergamon, Pompeii and Egypt, even the Tomb of Agamemnon, and the Palace at Knossos, believing that they too must figure into the psychical make-up of Rome. In the remaining gaps and margins I composed entirely new buildings with gardens, stairs and ramps connecting the various historical layers. As the drawing evolved Rome became something else. Through the combination and collision of structure, time and space an entirely new city sprang forth.

Over the course of a year my colleagues had nearly completed the revisions to their plates, while mine grew more intense and involved. As it developed, however, I realized the two-dimensional plan view could not express the depth, the layering, and extent of excavation I envisioned. Something else, some other drawing, I thought, must better illustrate the vision I had of Rome.

Immediately, I remembered the Carceri engravings of Piranesi: the so-called prisons; the dark, ominous, and limitless spaces; the fury of lines and scratches; grandeur, timelessness and vertigo; the inspiration of writers like De Quincey, Yourcenar and Updike, filmmakers like Eisenstein, and architects like Louis Kahn. These were the type of drawings needed to capture the spirit of my vision for the Campo, and compliment the plan still growing in front of me.

Over the next three years I imagined walking along the walls, scaling the towers and domes, climbing the steps, platforms and scaffolding within the plan. I sketched the ruins, the remnants of buildings and construction that might exist there. Some of the sketches evolved into larger drawings as there was always one more arch or wall to add, another pier, column or stair that was needed. It occurred to me that the project might never end. In fact, the other architects who had finished their revisions long ago still ask when I will be done. To this day I continue adding to the plan and drawing more perspectives.

The project for me has expanded well beyond its original scope and intention. With Nolli, Piranesi, Freud, the Ceasars and Popes on my mind, I find myself trying to document an entirely different city. The foundations and structures are identical with that place we call Rome. The history is the same. But in this place, the layers of stone and brick have coalesced with the city’s entire past, its memory and spirit.

It is a new kind of city; one of the imagination, but still very real, authentic. It is that psychical entity Freud describes; a strange yet vaguely familiar maze of streets and stairs, walls, columns, towers, and domes expanding in every direction.